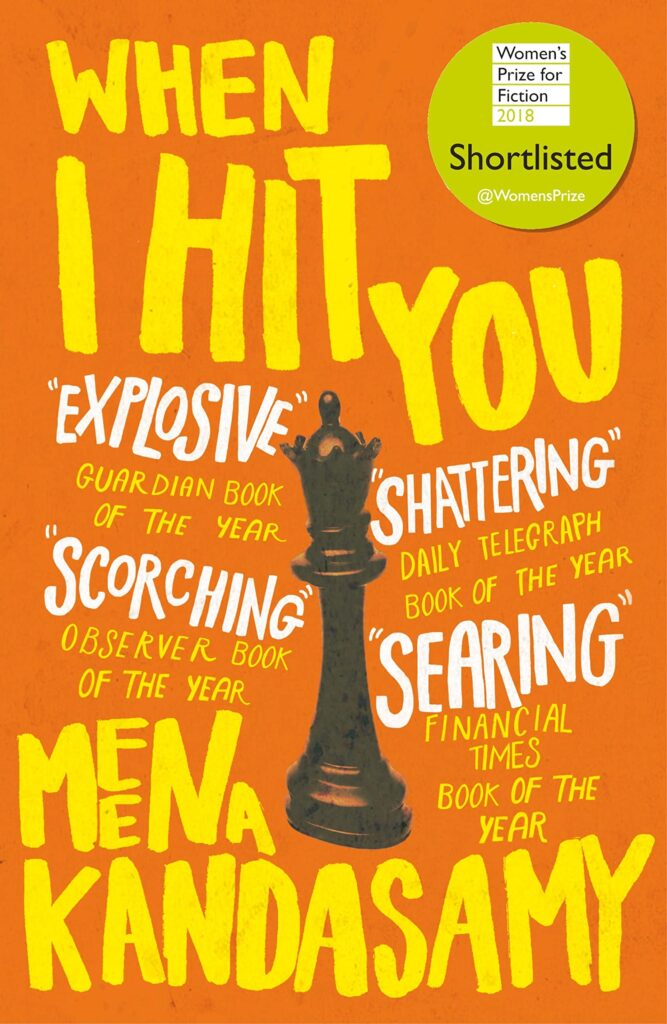

From the Women’s Prize Archives.

The brilliant Meena Kandasamy has been shortlisted for the 2018 Women’s Prize for Fiction for When I Hit You. Read on to find out why for Meena poetry is immediate and novels are a slow burn, and how meeting former female guerrillas and the poetry of Anne Sexton and Carol Ann Duffy have affected Meena’s writing.

Which female writers have influenced you most?

That is an endless, ongoing list that I’m most happy to share. Much of my introduction to poetry was the work of Kamala Das—confessional, brutal, sensual, stark—and in her words I could find a home for my own dreams, fears and body as a teenager. Reading her led me to devour female poets across times and landscapes—Anne Sexton’s Transformations and Carol Ann Duffy’s The World’s Wife both gave me the courage and the inspiration to attempt feminist retellings of Hindu/Tamil myths in Ms Militancy. In fiction likewise, I was enthralled by Arundhati Roy—reading her was so transformative—and her political writings allowed me the courage to be political and outspoken. I admire the work of Toni Morrison—the precision of her language and her wise way of capturing character. It also opened the world into reading African American writers: Gwendolyn Brooks, Alice Walker, Maya Angelou, Angela Davis. At various points in my life I dabbled in learning French and German—and even though I do not have any working knowledge of these languages that I can boast of, I was happy that this led me indirectly to read so much literature in translation. And they are all so damning and political—and in the best sense of the word. Elfriede Jelinek, Herta Muller, Juli Zeh, Ingeborg Bachmann among the female authors in German, and in French: Marguerite Duras and all of the French feminists: Luce Irigaray, Helene Cixous, Julia Kristeva. I also think that we often tend to list writers who are working in the same genres as us: poets and novelists—sometimes the influence comes from female intellectuals, artists, photographers.

You’re a poet as well as a novelist – which do you find most powerful and why?

That’s a tricky question! I still feel that nothing quite parallels the feeling of reading poetry to an appreciative and appropriate audience (like performing a protest poem at the site of a university lockdown and strike, or reading a feminist poem that connects with women across race and colour and language and nationality)! In that sense, the gratification for the writer is immediate, it is shared energy and community, it is a little like teaching, a little like organizing—you enter a zone of collective intimacy very, very quickly. The novel is a slow burn. It is seduction. Seduction with all your knowledge and manuals and study guides safely hidden away from your readers. To keep a reader with you—with every word, every turn of phrase, every chapter—is remarkable because as much as it is about telling a story, it is about earning trust. In that sense, writing a novel is an invitation for the reader into a landscape that you have either created or reimagined—and for this hospitality, they are willing to listen. That is enormous power. I do both, and I do essays too.

Did you make a specific personal choice not to write the safe and comfortable?

I would like to say “yes.” The truth is somewhat different: I doubt if there is any choice. I entered activism early. Even my translations are of political texts. I was writing from (what academics would call) the margins. It was inevitable that the writing would neither be safe and comfortable, nor conventional and formulaic.

When I Hit You is partially autobiographical – what effect did revisiting and writing this abuse and trauma have on you?

I do not really know. There was a part of me which was determined to not look at the hurt because it would be break me even more. To allow oneself to break is to validate an abuser. Once I walked out of the marriage, I immersed myself in finishing my first novel. I travelled widely. I was meeting former female guerrillas and documenting their experiences of war and sexual violence. I did everything that I could do to forget what I had been through. All that distance helped, I could get a degree of detachment. When I finally sat down to write the story my first priority was to the narration, to the language. I worked towards capturing the delicate, tenuous situation of a woman facing abuse, I was using the armour of plot to allow the woman’s defiance to sparkle. All that attention to the story let me to step outside of it, and I think, stepping outside is a way of telling oneself: Oh, I’m no longer trapped.

How do you think we can stop the cycle of trivialising violence against women, both in India and around the world?

#MeToo is a brilliant start—it has broken the taboo of silence, centered female voices, allowed us to share our experiences of abuse and call out the patriarchal, misogynist abuse of power. I think that we have to interrogate violence much more closely—domestic violence and sexual violence are one of its many manifestations. What happens within a man-woman relationship does not come from nowhere. If we in India are guilty of making millions of girls disappear before they are even born through sex-selective femicide—it shows how thoroughly devalued women are. If we pay women less, we are telling them they are less worthy. Not being treated as an equal is often the entry point to systemic oppression. It happens with race and ends up in slavery, it happens with caste and ends up in untouchability, it happens with ethnicity and ends up in civil war, it happens with class and ends up in all the horrors of late-stage capitalism. We need to fight that—and as a feminist I think we need to fight on all fronts.